David Ogilvy's foreword to Scientific Advertising

The full text of David Ogilvy's 1964 foreword to Scentific Advertising by his mentor Claude Hopkins. I bought an overpriced copy of the book so that you don't have to.

Here's my copy of the book

I’m a nut for David Ogilvy.

I will happily read anything that he ever wrote.

Whether it’s an agency wide memo from 1963 or a long copy ad for Rolls Royce, every time I read and re-read his work I learn something new.

One of Ogilvy’s great mentors was the early 20th century ad man Claude Hopkins.

Hopkins wrote the 1923 book Scientific Advertising which introduced the pubescent ad world to the benefits of informing advertising through testing and research rather than by opinion and instinct.

I’m not sure these teachings have been widely adopted even almost a century later. But they had a great influence on Ogilvy and he spread the gospel widely.

“Nobody should be allowed to have anything to do with advertising,” Ogilvy wrote, “until he has read this book seven times. It changed the course of my life."

I read Scientific Advertising many years ago after discovering it through one of Ogilvy's books. It’s a short read that’s still surprisingly useful and relevant. It’s available in the public domain and you can read it for free online (or there are umpteen editions available for a dollar or two on the Kindle store and elsewhere).

As a would-be Ogilvy completist, one of his works had always eluded me: the forward he wrote to the 1963 posthumous re-issue of Scientific Advertising.

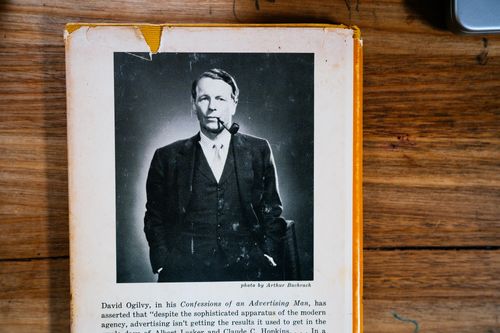

Confessions of An Advertising Man had been a surprise bestseller just a few years before and Ogilvy was at the height of his fame. His photo and blurb entirely dominate the back cover.

Even on AbeBooks and equivalent, copies are quite hard to find cost more than one should reasonably spend for the benefit of a few hundred words.

This edition was clearly a brazen effort at capitalising on Ogilvy's mid-60s fame

After thinking about it for a year or so, I recently ordered a copy from a rare bookseller in Aurora, Illinois (somewhere I have never been but which in my imagination looks a lot like a John Hughes film). I hope to save you from doing the same by posting Ogilvy’s foreword here.

This was published in just one edition of the book a decade before the current American copyright laws took effect in 1978. Ogilvy has been dead for 20 years. On that basis, I presume I’m not breaking any laws by posting this but do feel free to send a cease and desist notice via the usual channels.

Nobody, at any level, should be allowed to have anything to do do with advertising until he has read this book seven times.

Claude Hopkins wrote it in 1923. Rosser Reeves, bless him, gave it to me in 1938. Since then, I have given 379 copies to clients and colleagues.

Every time I see a bad advertisement, I say to myself, "The man who wrote this copy has never read Claude Hopkins."

If you read this book of his, you will never write another bad advertisement—and never approve one either.

Don't be put off by Hopkins' staccato, graceless style. When he was a boy he had to go to church five every Sunday, and knew most of the Bible by heart. This caused him to write with the brevity of the King James Version, but with none of its beauty. Don't be put off by his misuse of the word scientific. As Alfred Politz has pointed out, Hopkins "does not indicate the boundaries between direct findings from experimentation and conclusions arrived at by general observation and reasoning."

A few of his conclusions have been disproved by later research. For example, Dr. Gallup and Dr. Starch would not agree with Hopkins when he writes: "In every ad consider only new customers. People using your product are not going to read your ads."

Nor would Procter & Gamble now agree that "the most successful toothpaste advertiser never features tooth troubles in his headlines."

Hopkins believed that nobody with a college education could write copy for the millions. Perhaps that was because he had not been to college himself.

He thought that illustrations were a waste of space. Perhaps they were less important fifty years ago, when magazines and newspapers were thinner, and competition for the reader's attention less severe.

But forty-two years after Hopkins wrote this book, almost everybody would agree with the following conclusions:

"Almost any question can be answered, cheaply, quickly and finally, by a test campaign. And that's the way to answer them—not by arguments around a table."

"The only purpose of advertising is to make sales. It is profitable or unprofitable according to its actual sales."

"Ad-writers abandon their parts. They forget they are salesmen and try to be performers. Instead of sales, they seek applause."

"Don't try to be musing. Money spending is a serious matter."

"Whenever possible we introduce a personality into our ads. By making a man famous cue make his product famous."

“It is not uncommon for a change in headlines to multiply returns from five to ten times over."

Some say, 'Be very brief. People will read but little.' Would you say that to a salesman? Brief ads are never keyed. Every traced ad tells a complete story. The more you tell the more you sell."

"We try to give each advertiser a becoming style. He is given an individuality best suited to the people he addresses. To create the right individuality is a supreme accomplishment. Never weary of that part."

"Platitudes and generalities roll off the human understanding like water from a duck. Actual figures are not generally discounted. Specific facts, When stated, have their full weight and effect."

Claude Hopkins was born in 1866 and died in 1932. At seventeen he was a lay preacher, and his ambition was to become a clergyman. But he rebelled against his family's fundamentalist brand of religion, and got a job as a bookkeeper at $4-50 a week.

Not long afterwards he joined the Bissell Carpet Sweeper Company, and invented selling strategies which gave Bissell a virtual monopoly. Then to Swift as Advertising Manager. Then to Dr. Shoop's patent medicine company in Racine, where he persuaded his agency to let him write all the copy—not only his own account, but on several of the agency's other accounts as well, including Montgomery Ward and Schlitz Beer.

In 1908, when Hopkins was forty-one, he was hired by Albert Lasker to write copy for Lord & Thomas. Lasker paid him $185,000 a year—equivalent to $639,000 in today's money (N.B About $5m in 2019 money - OP). Hopkins earned every penny of it. He seldom stopped work before midnight, and was prodigiously fertile. From his typewriter came campaigns which made a long list of products famous and profitable. They include Pepsodent and Palmolive.

He was more than a copywriter in today's narrow sense of the word. He was a total advertising man. He invented ways to force distribution for new products. He invented test marketing. He invented sampling. He invented copy research. He invented brand images. He invented pre-empting the truth. And he wrote copy which sold merchandise.

His unique effectiveness was due to three things. First, he loved his work. Second, he was a showman. Third, he was an unrelenting practitioner of the experimental method—forever testing new ideas in search of better results.

Like most good copywriters, Hopkins had little facility. More than once, his first wife found him sitting on a park bench in the middle of the night, wracked with despair after days of failure to invent an idea which he thought strong enough to sell.

He used to say, "No argument in the world can ever compare with one dramatic demonstration." Which makes me think that he would have been as successful in television today as he was in print fifty years ago.

You may deplore Hopkins, on the ground that he devoted his life to bamboozling the American public. But autres temps, autres moeurs. Before he died, Hopkins himself had come to regret some of his early copy for patent medicines.

Hopkins was a shy man who spoke with a strong lisp. But he was a superb raconteur and a tremendous after-dinner speaker. He always wore fuchsia in his buttonhole. He chewed dry licorice root, to cut down on smoking.

He was notoriously stingy, but his second wife persuaded him to buy an ocean-going yacht, to employ an army of gardeners on their estate, and to buy splendid Louis XVI furniture. She filled their vast house with an endless procession of guests. Her cook was famous. And she played Scarlatti to Hopkins for hours at a time. Today, thirty-three years after his death, she is still alive and vigorous.

In later life, Hopkins came to resent the fact that he had made so many of his clients richer than himself. And he was interested in nothing but advertising. There is macabre pathos in the last sentence of his autobiography: "The happiest are those who live closest to nature, an essential to advertising success."

DAVID OGILVY

December 1965